In 2007, the blockade imposed by Israel and Egypt in Gaza transformed the Strip into an area entirely dependent on humanitarian aid and external support, with the movement of people and goods under Israeli and Egyptian control. The 7 October attack on Israel in 2023 and the consequent war on Gaza exacerbated the humanitarian crisis, leading to critical levels of food insecurity, internal displacement, and the spread of infectious diseases. Immediately after the attack, Israel tightened the blockade, cutting off water and electricity supplies, and reducing the aid access compared to the pre-war period. However, even before 7 October, the management of humanitarian aid in the Strip made Gaza an exception compared to other conflict zones in the region and beyond. Gaza’s exceptionality in terms of aid access and implementation can be summarised by four main factors.

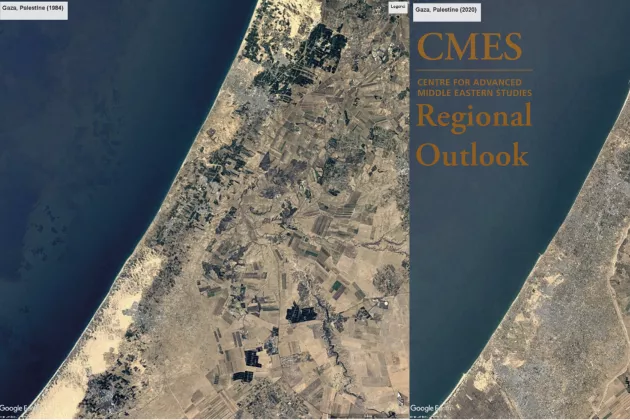

- The geographical “isolation” of the Strip, linked to Israel's occupation and blockade, with all borders controlled by Israel (and one by Egypt) for the transit of goods and people (see map below).

- The political circumstances surrounding Hamas, which controls the Strip as de facto authority but is boycotted by the US and the EU, both of which enforce a “no-contact policy” with Hamas.

- The lack of local ownership in aid coordination and management, resulting in the consequent marginalization of Hamas’ institutions and civil society organisations in aid interventions, including recurring reconstruction process.

- The prolonged humanitarian assistance and the absence of development goals.

These components have created a highly politicised space of aid interventions, which has become even more evident after the war began.

The Obstacles of Delivering Aid Into Gaza

The Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) is the Israeli agency in charge of tracking and recording all aid transferred into Gaza via land, aerial and maritime routes. Prior to 7 October, the main crossing points of the Gaza Strip were Rafah and Kerem Shalom in the south and Erez in the north (see map below). On 7 May 2024, Israeli operations in Rafah led to the closure of this crucial crossing point for humanitarian aid. Before the ground operation, the Rafah crossing was under Egyptian jurisdiction, which largely denied entry to items classified as “dual-use” by Israel. By August 2024 (see the OCHA map), access to pre-approved humanitarian aid was restricted to Kerem Shalom, Erez (open since 1 August 2024) and Gate 96 (north of Wadi Gaza).

Israeli authorities claim that there is no limit on the amount of aid entering Gaza. However, several factors and policy choices made by Israel directly affect humanitarian operations, preventing the access and safe distribution of a sufficient volume of aid. The major limitations include:

- Failing to secure safe zones for aid distribution and humanitarian workers, particularly in northern Gaza. Human Rights Watch reports that more than 250 aid workers have been killed in Gaza since 7 October. COGAT reports “IDF local tactical pauses” to enable the movement of humanitarian aid. Ongoing attacks on humanitarian workers violate international humanitarian law.

- Blocking the use of Ashdod Port or other ports in Israel for the entry of international aid. As a result, aid agencies must import goods via Port Said in Egypt, 200 km (124 miles) away from the Rafah Crossing, or via Al Arish airport (45 km from Gaza). An exception was the US mission Joint Logistic Over-the-Shore (JLOTS) , which delivered humanitarian aid to Gaza from May to July 2024.

- Refusing to restore the supply of electricity or resume the full water supply, both purchased by the Palestinian Authority from Israel’s Electric Corporation and Mekorot, which Israel cut off in the days following 7 October. Israel also continues to block the entry of industrial fuel for Gaza’s power plant.

- Systematically denying access of humanitarian agencies, particularly to areas north of Wadi Gaza. Access to aid in the north via the Salah ad Din Road requires coordination with the Israeli military.

- Refusing to open additional crossings to Gaza, including in the north. Since mid-March 2024, some trucks entered northern Gaza through an entry point referred to as “Gate 96”. A third northern crossing point was opened in May 2024, “Erez West”, but closed at the beginning of August, while Rafah remains closed since May 2024.

The Destruction of Gaza and Challenges for Reconstruction

While the immediate priority is the humanitarian response, recovery and reconstruction in the medium and long term will require a significant political and financial resources. Typically, post-conflict recovery and reconstruction plans align with the political objectives of the dominant actors. However, in Gaza, several questions arise for any hypothetical reconstruction plan.

Is reconstruction feasible?

In April 2024, an initial report from the World Bank estimated that the cost of damage to critical infrastructure in Gaza was around $18.5 billion. Satellite images provide valuable information on the extent of Gaza's destruction in terms of infrastructure and lands. According to the Housing, Land and Property technical working group, 83% of the population has been displaced, and at least 370,000 housing units in Gaza have been damaged, with 79,000 completely destroyed.

Who will pay the price of the destruction?

In August 2024, a meeting of donor countries and international charities in Ramallah was organised to secure and collect financial aid for the UN Development and Environment Programmes and the Palestinian Authority. Before October 2023, the EU, the US, the Gulf States and Japan were among the major donors in the Strip. Qatar played a crucial in various reconstruction phases, investing in infrastructure, roads, hospitals, and housing complexes while bypassing the mainstream “the no-contact” policy with Hamas. However, it is now time for donors to impose sustainable political conditions for the reconstruction, rather than aligning humanitarian response and recovery with Israeli military strategy and occupation as was done before.

How can reconstruction be implemented?

Israel launched its ground invasion of the Gaza Strip after 7 October without a clear plan for the territory or the population afterwards. The Biden administration encouraged Egypt, the UAE, and Morocco to deploy a joint Arab peacekeeping force in the territory to secure Gaza until a security and political Palestinian presence can be re-established. In Israel, different options have been proposed, reflecting a lack of internal cohesion in terms on post-war scenarios. One option is for Israel to maintain security control over Gaza and entrust the civilian affairs to a coalition made of the US, EU and Arab administration, while Israeli Defence Minister Gallant has proposed a “non-hostile” Palestinian governing alternative.

In conclusion, any reconstruction plan – beyond its financial efforts – will require a sustainable political solution, in which donors’ policies for recovery and reconstruction prioritise the real needs of the local population, transforming Gaza into a positive exception.