Several Qur’an burnings occurred in Sweden this summer leading to protests in Muslim-majority countries. The repercussions might be limited in the short-term with the strong reactions from governments and Islamic organisations mostly being of a symbolic nature. However, the increasing perception in many countries in the MENA region that Swedish state and society are hostile to Islam endangers Sweden’s historical standing in the region as a neutral arbiter, provider of crucial humanitarian aid and promoter of human rights and democracy.

A response to this perception requires not only diplomatic initiatives but needs to address the increasing normalisation of Islamophobia in some parts of Swedish politics. Current discussions to prohibit the desecration of sacred scriptures are insufficient. A more robust societal debate is required to address the increase in exclusionary discourses targeting Muslim minorities.

Danish-Swedish far-right activist Rasmus Paludan began a series of public burnings of the Qur’an in April 2022 which led to riots across Sweden. These were followed by Iraqi refugee Salwan Momika’s burning of the Qur’an in front of the Stockholm Mosque on 28 June 2023, on Eid al-Adha, the major Islamic holiday which concludes the pilgrimage to Mecca. He repeated this act in Stockholm on 20 and 31 July. On 21 August, he submitted several requests to repeat the Qur’an burnings in other Swedish cities. Unlike on previous occasions when the Swedish police granted him permission, this time they refused to do so citing concerns of maintaining public security and peace. Momika arrived as a refugee in Sweden. He has a Christian background but is a self-professed atheist and critic of Islam. Before his arrival in Sweden, he fought against ISIS in Iraq as part of a Christian militia within the Popular Mobilization Forces. The Swedish government has condemned these acts of burning the Qur’an while equally pointing to Sweden’s broad understanding of freedom of expression which provides few legal options to prevent such acts.

Why are these burnings of the Qur’an so offensive to many Muslims?

The Qur’an is seen as the exact Word of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century. This means that Muhammad is not considered to be the author but merely the recipient of a series of divine revelations, which were collected in the Qur’an after his death. The reverence many Muslims hold towards the Qur’an is evident in the way they treat the Qur’an as a printed text: many perform ritual ablutions before reading it, kiss the cover of the Qur’an as a sign of respect, never put the Qur’an on the ground and always place it on top of a pile of books. Burning a copy of the Qur’an is equally considered blasphemous because a book that contains the Word of God is desecrated.

While the religious sensitivities many Muslims hold around the Qur’an explain some of the strong reactions, Paludan and Momika also sought to deliberately provoke Muslims by attacking something many of them consider divine and sacred. These acts are meant to further the far-right agenda of presenting Muslims as followers of a religion that is at odds with fundamental civil and human rights and hence alien to European cultural and political traditions. Such exclusionary aims targeting Muslims for political gains are evident in the timing of Paludan’s emergence in the Swedish public sphere before the Swedish general elections in September 2022. Momika’s motivations for the Qur’an burnings are less obvious – apart from his self-professed atheism and rejection of Islam.

Reactions in the Middle East and beyond

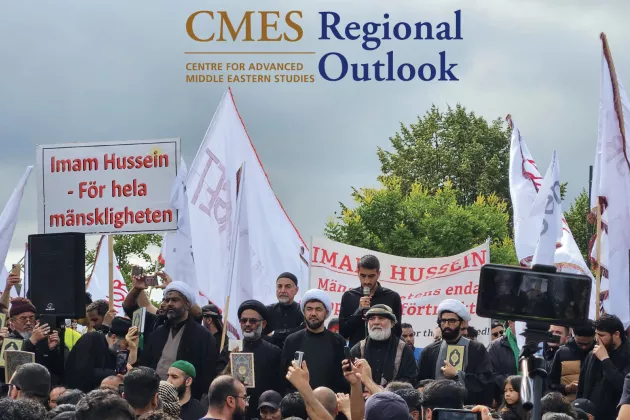

The reactions in most countries have mostly been diplomatic, symbolic, and temporary, ranging from statements criticising the incidents (Turkey, Jordan, Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia), summoning the Swedish ambassador to the country (Iraq), recalling the ambassador from Sweden for an indefinite period (Morocco) to ending the activities of Swedish humanitarian organisations (Afghanistan). The Organisation for Islamic Cooperation, a Saudi-based intergovernmental organisations of 57 mostly Muslim-majority member states, invited its member states to take appropriate actions in their relations to Sweden, to encourage cooperation with civil society organisations in Sweden to file local lawsuits and to take their cases to international judicial bodies. The United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a motion against religious hatred and incitement to discrimination, hostility, or violence. These various diplomatic declarations were also accompanied by protests in countries such as Pakistan and Iran. Kuwait commissioned the printing of 100,000 Swedish translations of the Qur’an for their distribution in Sweden. Among the more serious reactions was the storming of the Swedish embassy in Baghdad on 29 June and the non-fatal shooting of a Turkish employee at the Swedish consulate in Izmir on 1 August.

Short-, mid- and long-term consequences

Many of these diplomatic and symbolic gestures can be interpreted as efforts by rulers and governments of Muslim-majority countries to gain domestic legitimacy and to raise their geopolitical profiles. Equally, they reflect domestic power struggles: many protesters storming the Swedish embassy in Baghdad were followers of the populist clerical opposition leader Moqtada al-Sadr who used the massive global responses to the burnings to gain further political capital in Iraq. Social media campaigns amplifying the impact of the burnings globally have been attributed to state actors interested in obstructing Sweden’s NATO membership bid. However, the recent incidents and the growing perception in many Muslim-majority countries that Sweden is an Islamophobic country have various consequences:

- In the short-term, these incidents create security risks for Swedish citizens and interest in the region.

- In the mid-term, they may harm Sweden’s long-term security interests by delaying its accession to NATO, as Turkish president Erdogan’s response to the Qur’an burning in front of the Turkish embassy in Stockholm on 21 January 2023 illustrates.

- In the long-term, the risk of Sweden gaining the reputation as an Islamophobic country challenges its soft power in the MENA region and in Muslim-majority contexts globally and its role as a neutral arbiter, as a promoter of human rights and democracy and as a key player in global humanitarian aid efforts.

This article is part of CMES Regional Outlook on Current Affairs series. The author is responsible for the analysis and views expressed in this publication.